This isn't like a normal essay, where you'd read linearly from top to bottom - instead, the essay is made up of small sections that are connected together - the connections are shown at the start and end of each section, in links that you should click on them to jump to that section. For example, down below you can see that this first section is linked to "required hedging".

If you're using a big enough screen, I've added something to the side of the page that'll give you a history of which sections you've clicked on, that should make it a bit easier to navigate.

I wouldn't recommend trying to read this from top to bottom like you normally would, I haven't written it with that in mind, I doubt it will make any sense.

Click on "required hedging" to start, then you can come back to the "An app designed for conversation" section later:

Links from this section:

Required hedging

Links to this section:

Friends before have told me I sound too confident when I say things, so much so that they just believe me by default, and that I should always say "I think" more often, so I'll get my hedging in now, and say:

I'm not 100% sure of anything I say here, this is just what I think, please don't take it as gospel.

A lot of this, probably even most of it, isn't my original thoughts, just me putting together things I've read, but I hope it'll still be useful.

Links from this section:

Friends are important; the Anatomy of Friendship

Links to this section:

Robin Dunbar, of number fame, has written more than 1 academic paper in his life.

The one I'm interested in here is his Anatomy of Friendship - I need to thank @choosy_mom for bringing my attention to it.

In it, he describes just how important friends are to people, and to their health; it's a lot more than I thought:

Over the past two decades, considerable evidence has emerged to suggest that the most important factor influencing our happiness, mental well-being, physical health, and even mortality risk, not to mention the morbidity and mortality of our children, is the size and quality of our friendship circles [..] Friends provide moral and emotional support, as well as protection from external threats and the stresses of living in groups, not to mention practical and economic aid when the need arises.

(this is a really interesting paper, and if you want to learn more about this whole topic, it has 222 references, so there's a lot to dig your teeth into)

Summary

Links to this section:

The short version of this is:

Talking to people on the internet right now is very different to talking to them in person, and that's not good for us, but it could be more similar to face-to-face interaction.

This is pretty much a long list of "things I don't like about how we talk to each-other online".

The first of many quotes from Adam Elkus:

Current social networks do not really fit with evolved human sociality. Could you build better ones? [...] We’re growing more rather than less online as time goes on, and online is becoming more rather than less game-like. Absent less destructive ways to interact with each other, our social media woes will only get worse.

And from someone called Ed, in this essay by Clay Shirky, A group is its own worst enemy:

Today, hardly anybody really studies how to design software for human-to-human interaction. The field of social software design is in its infancy. In fact, we’re not even at the point yet where the software developers developing social software realize that they need to think about the sociology and the anthropology of the group that will be using their software, so many of them just throw things together and allow themselves to be surprised by the social interactions that develop around their software.

In his "Game Design Patterns for Building Friendships" talk, Daniel Cook mentions a lot of what I'm going to talk about myself here.

How we talk online isn't a substitute for face-to-face

Links to this section:

Dunbar's paper also said this:

Participants in a diary study were asked to evaluate the quality of the interactions they had had with their five best friends each day: face-to-face and Skype outperformed the phone and text-based channels [texting, SMS, email and social networking sites] by a considerable margin. Importantly, perhaps, interactions that involved laughter, whether real or digital (e.g., emoticons), were rated more highly than those that did not. What face-to-face and Skype interactions share is a sense of copresence (being in the same room together); in addition, they provide visual cues that allow us to monitor and adjust the flow of the interaction more effectively (thereby avoiding faux pas, for example) and radically increase the speed of interaction (facilitating repartee, and hence laughter). Single-channel (e.g., phone) or text-based media are simply too impoverished or too slow

I don't think I'd be as anti-phone-calls as Dunbar is here, there's some evidence that speech by itself is enough for connection, see the "Speech is the most important bit" section.

How we talk to eachother on our different websites and apps just isn't a substitute for face-to-face interaction with people, and it's harder to make friends with people using them, too.

And since friendships are so important to our physical and mental health, and we seem to be inexorably talking to people more and more online instead of in-person, I think this might have pretty big effects on us.

Jonah Bennett brings up some of the social effects in a call to action:

Teens date less. They have less sex. They drink less. The rate of illegal drug use is way down, and they don’t party. But this collapse in social vice is not because they’ve taken solemn vows of moral purity. It’s because they don’t leave the house and don’t have physical, embodied community.

As does Brad Hunter in The Subtle Benefits of Face-To-Face Communication:

While we maximize the abilities and benefits of [the Internet, e-mail, instant messaging, cell phones, pagers, faxes, and the World Wide Web], we need to remember to engage in local communities and physical interaction for the subtle and important benefits which they provide.

And Sherry Turkle (what I'm complaining about here seems almost identical to her Reclaiming Conversation):

We were increasingly willing to talk to machines, even about intimate matters. And increasingly, with the rise of mobile devices, we were paying attention to our phones rather than each other. In both cases, there was a flight from face-to-face conversation. In both cases, technology was encouraging us to forget that the essence of conversation is one where human meanings are understood, where empathy is engaged.

[..]

Our willingness to talk to machines is a part of a culture of forgetting that challenges psychotherapy today. What we’re forgetting is what makes people special, what makes conversation authentic, what makes it human, what makes psychotherapy the talking cure.These are some of the consequences of expecting more from technology than technology can offer. I’ve also said that in our flight from conversation, we expect less from each other. Here, mobile communication and social media are key actors. Of course, we don’t live in a silent world. We talk to each other. And we communicate online almost all the time. But we’re always distracted by the worlds on our phones, and it’s become more common to go to great lengths to avoid a certain kind of conversation: those that are spontaneous and face-to-face and require our full attention, those in which people go off on a tangent and circle back in unpredictable and self-revealing ways. In other words, what people are fleeing is the kind of conversation that talk therapy tries to promote, the kind in which intimacy flourishes and empathy thrives.

[..]

Consider Vanessa, a college junior who talks about her trouble sitting alone with her thoughts and her habit of using the phone to avoid talking to other people. “As long as I have my phone, I’d never just sit alone and think,” she says. “My phone is my safety mechanism from having to talk to new people, or letting my mind wander. I know that this is bad, but texting to pass the time is a way of life.”

That's not to say online communication has no advantages; one is

Online interactions often provide anonymity and an ability to present ourselves differently than we might ordinarily. The predominance of written communication gives us a way to edit our utterances until they fit the image we want to project, something which is not quite so simple in a real time environment. Since our words are our only connection to others, it is much easier to be duplicitous or even self-deluding.

Now, I'm not saying it's impossible to make and stay friends with people on the Internet, just that it's harder than it needs to be.

Luckily for me, the Anatomy of Friendship gave me some Scientific Evidence backing up thoughts I'd been having for a while, and pointed me in the direction of lots of other things I could read about friendship.

Especially since something doesn't exist unless Science proves it does.

Links from this section:

We can get closer to face-to-face

Links to this section:

All is not lost, the skies haven't fallen, the gates of Hell haven't opened.

We can do better than our current systems, and we already are using some better ones than just plain-text communication, like Snapchat, Houseparty or voice messages on Facebook Messenger.

But first, to get pointed in the right direction, to find out what to make, I think it's helpful to explore some of the problems with our existing websites and apps - or, what specifically makes it different from talking to people face-to-face.

Important caveats

Just because when you use a plow to fish it doesn't make a good fishing rod, that doesn't mean the plow is a useless tool altogether, just that it has its strengths and its weaknesses; Twitter, Reddit, Facebook, Discord, they all have their strengths and weaknesses too, I just don't think "making and maintaining friendships" are definitely some of their strengths.

Everything has a time and a place - maybe Twitter is good for getting up to the minute breaking news on some event, Reddit for lots of people congregating on one page to talk about a specific topic, but neither of them are perfect for conversations.

And, not everything is monocausal and specifically results from whatever shit I'm on about at any given time.

Also, lots of these might just be problems I have, things only I experience, the hangups I have with them. Maybe I'm using the websites wrong. Lets see:

Links from this section:

Media naturalness theory

Links to this section:

One of those things Dunbar's paper pointed me towards was Ned Kock's Media naturalness theory, explained more in this paper (The Psychobiological Model: Towards a New Theory of Computer-Mediated Communication Based on Darwinian Evolution) - this one's free to download and read.

The short version of it is "the more similar a communication medium is to face-to-face communication, the less effort it takes for people to use, and the higher quality it is", but there's far more good information in it than that. If that sounds obvious, there are some competing theories, like social presence and media richness, which also sound obvious, but have issues with them:

Social presence is how aware you are of the other person -

communication is effective if the communication medium has the appropriate social presence required for the level of interpersonal involvement required for a task

It's 1-dimensional - face-to-face has the most presence, and written text the least.

Media richness is similar - it categorises communications mediums by how well they can carry non-verbal cues, give you rapid feedback, let you convey your personality traits, and support natural language.

The main problem with these 2 theories is that a medium can have too much social presence - you can be too socially present for it to feel natural - it can be too rich.

The more natural a communication medium is, the better it is

Links to this section:

"Natural" means how similar it is to face-to-face interaction.

Kock says there are 5 key elements of face-to-face communication, broken down into 2 axes - the space-time axis, and the expressive-perceptual dimension:

- Colocation, so people can share the same context. and see and hear eachother

- Synchronicity, so they can quickly exchange communication stimuli

- Expressing and seeing facial expressions

- Expressing and seeing body language

- Speaking, and listening to speech

Colocation and synchronicity are the space-time dimension, the last 3 the expressive-perceptual dimension

He argues that, a communication medium that has the most of those elements is the most natural one.

Links from this section:

Text is slow

Links to this section:

Conveying a message to someone over text is just so much slower than speaking it - paraphrasing the paper:

the number of words that an individual can convey per minute is about 18 times higher face-to-face than over e-mail in complex collaborative tasks, and, when you control for text being more time consuming to type than it is to read aloud, about 10 times higher

Links from this section:

Speech is the most important bit

Links to this section:

Because the cost of evolving the ability to speak was so high - it made us far more likely to choke (you'll need to read the paper for more info) - higher than any other naturalness element, he predicts that how much a medium supports speech contributes far more to the naturalness of a medium than any other element, so it's the most important thing to include in a communication medium.

[this suggests] that suppressing the ability to convey and listen to speech would substantially affect the naturalness of a medium, more than suppressing the ability to use facial expressions and body language

...

this is interesting from a [communication medium] design perspective, because it begs the question as to whether video-conferencing [...] is much better than audio-conferencing alone in terms of cognitive effort required. particularly given the substantial technical difficulties and costs associated with adding a video component to an audio-only channel. According to the theoretical perspective proposed here, it should not be; this expectation has been supported in the past by empirical research. Nor, according to the theoretical perspective proposed here, should face-to-face interaction be much better than video-conferencing, as long as the audio channel is of good enough quality

This article makes the same point:

we asked people to connect with a stranger by discussing several meaningful questions (e.g., “Is there something you’ve dreamed of doing for a long time? Why haven’t you done it?”), either by texting in real time during a live chat, talking using only audio, or talking over video chat

[..] Being able to see another person, in short, did not make people feel any more connected than if they simply talked with them. A sense of connection does not seem to come from being able see another person but rather from hearing another person’s voice. This is consistent with several other findings suggesting that a person’s voice is really the signal that creates understanding and connection.

our data suggest that you’re apt to overestimate how awkward it will feel to talk on the phone, or to underestimate how connected that will make you feel—and as a result you may send text-based messages when voice would be more beneficial. So, take a little more time to talk to others than you might be inclined to. You—and those you talk to—are likely to feel better as a result

As does this article.

Favourite part of twitter spaces is hearing someone’s voice for the first time and getting a whole new understanding of them as a person

A voice adds a lot of character and life to a person

My friend Kat made this point today and suggested I include it here: more and more, people my age talk to each-other with async text messages, but in the past everyone called more often instead. I joined a bowls and tennis club last week, but I wanted to join for weeks, and I kept putting off calling them to ask to join; I, and from I can tell, many other people too, are almost getting scared of talking to people on the phone and think it will be awkward, we do it so little. And since we do it so infrequently, we get worse at it, put it off even more, all a vicious cycle.

I asked a friend something on Facebook recently, and she didn't reply for a while. I didn't even think to call her to find out what she thought, I just sat and stewed. This is worse, it's not that I think to call and reject the idea, I never even think of it as an option in the first place.

we asked people to think of an old friend they had not interacted with in a while, but with whom they would like to reconnect. These people then imagined how these interactions would make them feel if they typed to their old friend (over email) or talked to their old friend (over the phone). Results were mixed. Although people expected to feel more connected to their old friend when talking compared to typing, they also expected to feel more awkward when talking compared to typing. When they were asked to choose which media they would prefer to use, the anticipated costs of talking seemed to loom large: The majority said they would rather just type to their old friend

Somehow, literally the day after I wrote the previous paragraphs, me and Kat were organising a trip we're taking this Summer, and we spent about an hour doing it over Facebook messages, completely forgetting our previous conversation. Afterwards I realised our mistake and we agreed next time to remember. Later on that week, we had a particularly nasty bug at work that 5 or 6 of us were discussing, trying to figure out the cause and how to fix it, all over Slack. Remembering the earlier silly mistake, I got us all talking on Zoom instead, and we found the root issue (it turned out to be a combination something I had done 2 months ago, something an intern did 2 weeks ago, and the day's date beginning with a 2, and not a 1) and agreed on a way to fix it, far quicker than we would in text.

And now, after a few more Zoom calls at work, this is from one of our sprint retrospectives:

Another possible reason people might not like phone calls or audio messages is that they're an inconvenience, an imposition that someone else is making on your well-ordered life or forcing you to make for their benefit - you need to take time out of your day to listen to them, or do speak back to them. To that, all I can say is there's a lot more to life than convenience, the point of life is not to minimise discomfort, or to optimise your life to the fullest extent.

It's very stupid to use a hypothetical strawman of fictional media that exists only in your head as examples for your argument. Think back to TV shows from 20 years ago, characters mainly called someone to talk to them, they didn't send a text. Nowadays, they text instead.

I would note that it's not just relatively old TV shows that people make phone calls in, I talk to my parents every week over the phone too. The older I get, the more I realise just how wise older people can be sometimes:

take a little more time to talk to others than you might be inclined to. You—and those you talk to—are likely to feel better as a result

Economists talk about how government fiscal policy crowds out public investment. I think the rise of sync text services is crowding out sync phone calls, which are far more life-affirming for us.

That sounded a bit stilted and cold, I'll try that again.

Phone calls are just more human than text messages.

Links from this section:

Only 4 people can really have a conversation

Links to this section:

One of the really interesting things I found in Dunbar's paper is that apparently only 4 people can really have a conversation with each-other - if a 5th person joins in, the conversation will probably break up into 2 smaller ones pretty quickly. I think that happened with me and some friends last week, actually.

Being able to understand your own mental state (like emotions, beliefs, knowledge) and intentions, and other people's, is called theory of mind - we're not born with it, we have to develop it as we grow up.

Theory of mind is the 1st level of something called mentalising - knowing that if you're talking to Alice, she has her own knowledge, her own beliefs, .. - and there are higher levels of it too, like "I know that you think that Alice wonders if Bob supposes that Charlie believes that pigs can fly", and the higher you get, the harder they are for people to do, and for you to understand. You probably had to think through that example; I did.

And conversations seem to be limited to 4 people because we can't really go beyond 5 levels of mentalising (including our own mental state) - "I know that you think that Alice wonders if Bob supposes that Charlie believes that pigs can fly" is pretty much our limit.

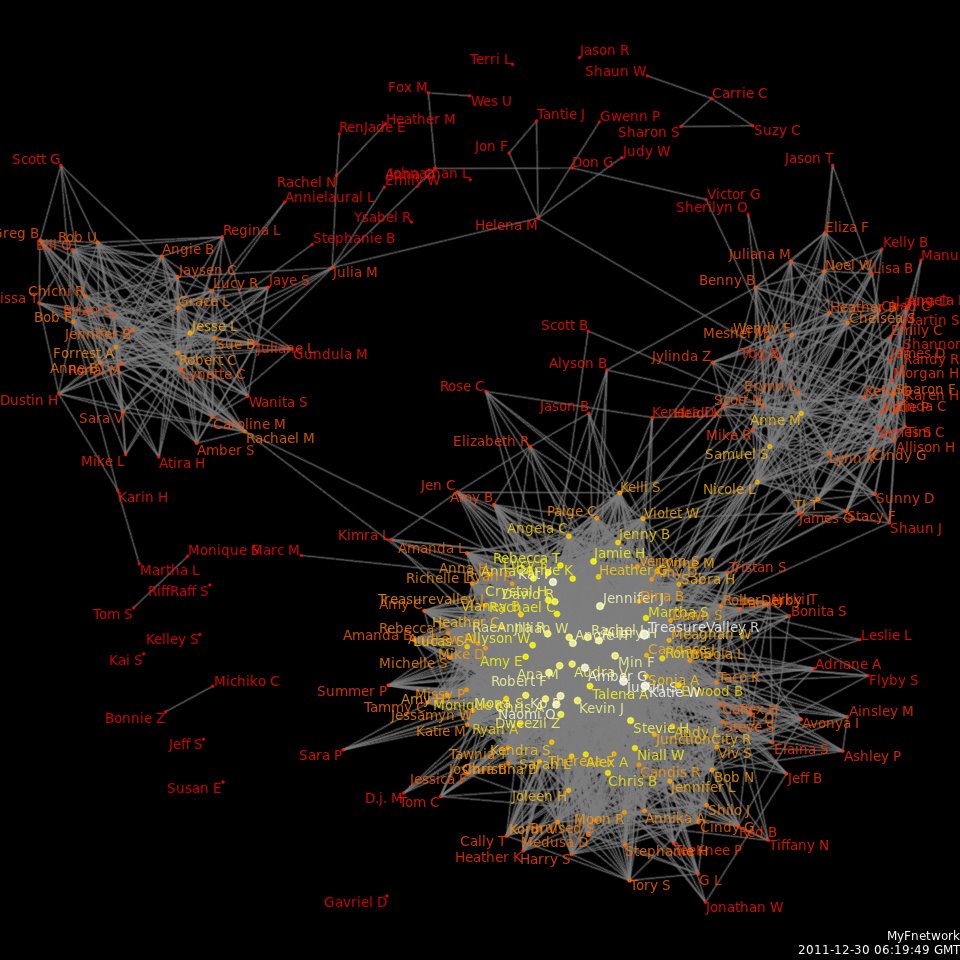

Visually, it's a bit like this "complete graph" K4 from Wolfram Alpha:

Even in conversations in plays, TV dramas and films you can see the limit, and if you're discussing the mindstate of someone who isn't present, the conversation is limited to 3 people, not 4! - this is true even in Shakespeare's plays, surprisingly - at most only 4 people have a conversation, and only 3 do if they're discussing someone else's state of mind.

From Dunbar's The small world of Shakespeare's plays:

Shakespearean dramas are structured in a very specific way that mirrors patterns observed in real human interactions. Characters are connected by a small number of degrees of separation, generally no more than 2. Nonetheless, social connections are highly clustered, as in real human behavior. Onstage interactions generally consist of cliques of four or fewer individuals, as in real human conversations. This limit is inflexible and maintained even as the total number of characters in the story increases. Thus, increasing the total number of characters necessitates increasing the number of different cliques, so the drama becomes less richly connected with increasing overall size. This sets an upper limit on the total number of characters in one play--30 to 40---that is remarkably similar to those observed in hunter-gatherer societies, and in people's social contacts in contemporary society. The reasons for the size regularities may be parallel in the two cases; as the size increases, the connectance decreases to the point that the network fissions (groups) or becomes incoherent (plays).

No body language

Links to this section:

People say between 0 < x < 100% of communication is through body language, and you very obviously don't get that at all through text.

This is so obvious it almost doesn't bear mentioning, but I thought I might as well cover all my bases.

It might not be very important anyway, compared to the other differences - we know speech is far more important than body language.

Links from this section:

No tone, or emotion

Links to this section:

At least in non-tonal languages, we can express quite a lot of our feelings and emotions through the tone of the words we say - again, pretty obvious.

You can imagine or remember the problems that come from that (there are so many, you can just imagine them yourselves), the misunderstandings, the ambiguities, the complications.

This is anthropomorphizing evolution a bit, but we're not made to communicate with people through writing, we're made to do it with speech - you learn how to speak growing up, but you need to be taught how to read and write (occasionally, kids will learn by themselves, but that's not very common).

I don't like how you can't do that in text, not as fluidly anyway - you can use CAPITALS or, if you're lucky enough, italics or bold, or, in most comms systems these days, emojis 😀 - but they have their issues as well (if you don't use them at every opportunity, think why you don't).

And when they are ambiguities, misunderstandings and in the like in speech, when your friend misunderstands something you say, you can clarify or correct them straight away, and go "no no, I meant xyz, not abc" and get everything cleared up really quickly - the synchronicity of speech lets that happen. Unfortunately, we now largely use async writing to communicate, the worst possible combination.

In written word there is almost no perceptible difference between an off-hand remark and a deeply held view.

In spoken word the difference is very striking.

Links from this section:

Most text signals are explicit & intentional

Links to this section:

Almost all signals that you can use to communicate something through text are intentional, you communicate something because you intended to, you explicitly meant to communicate it - see the difference between laughing, and typing "lol" or pressing the "laugh" emoji. (also, doesn't the sound of a laugh feel far more natural, more real?)

I think the only implicit signal you can send is whether or not you reply to someone, that's about it, and replying is quite a serious thing to do - how often have you scrolled past something you didn't like, didn't agree with, did like, thought was funny, loved more than seeing your puppy for the first time after a hard day at work, but not said anything? I'd say, probably fairly often.

If you were talking to someone in-person, your face could show that you didn't like what they said, or maybe you'd scrunch your eyes up if what they said confused you somehow - if you "react" to a friend's message on Facebook, you must explicitly choose to react, to say "yes that was funny", it's not natural, it doesn't just happen, like it could in-person.

Emojis are a step in showing tone, but they're also explicitly intentional.

You only send replies to people because you want them to read what you say, so if you explicitly say "I liked that!" you want them to know that you liked it - it feels more fake to me, more inauthentic, because an in-person reaction isn't guaranteed to be intentional, it's not just done because you want them to see it.

Brian D. Earp has a really good thread about this on Twitter - he's actually talking about moral outrage specifically, but I think this is just an instance of a more general issue - which I'll quote in full in-case he ever deletes it or his account:

I have a hypothesis about what might contribute to moral outrage being such a big thing on social media. Imagine I’m sitting in a room of 30 people & I make a dramatic statement about how outraged I am about X. And say 5 people cheer in response (analogous to liking or RT). But suppose the other 25 ppl kind of stare at the table, or give me a weird look or roll their eyes, or in some other way (relatively) passively express that they think I’m kind of over-doing it or maybe not being as nuanced or charitable or whatever as I should be. IRL we get this kind of ‘passive negative’ feedback when we act morally outraged about certain things, at least sometimes. Now, a few people in the room might clear their throat and actively say, “Hey, maybe it’s more complicated than that” and on Twitter there is a mechanism for that: comments

But it’s pretty costly to leave a comment pushing back against someone’s seemingly excessive or inadequately grounded moral outrage, and so most ppl probably just read the tweet and silently move on w their day. And there is no icon on Twitter that registers passive disapproval.

So it seems like we’re missing one of the major IRL pieces of social information that perhaps our outrage needs to be in some way tempered, or not everyone is on board, or maybe we should consider a different perspective.

If Twitter collected data of people who read or clicked on a tweet, but did NOT like it or retweet it (nor go so far as write a contrary comment), and converted this into an emoji of a neutral (or some kind of mildly disapproving?) face, this might majorly tamp down on viral moral outrage that is fueled by likes and retweet’s from a small subset of the ‘people in the room

Jesse Singal's also talked about it here, as has Devon Zuegel, and Marc Andreessen, in his interview with Niccolo Soldo - he calls it passive disapproval.

I think this is a big part of why, a lot of the time when I ask my friends a question on Facebook Messenger, they'll all read it, but no one will say anything. It keeps happening, over and over again, and it's very demoralising, thinking no one will answer your questions a lot of the time. It makes me not want to ask in the first place, and I wonder "what's the point of trying to talk to them, if they won't say anything back?"

Example: me and Codex

Links to this section:

A while ago, Codex replied to something I said, and I thought it was a but funny, I smirked. But I didn't reply to tell him that - "hey man, I just smirked when I read what you said", who would say that?

So all I could do was like it. Incredibly low-information signal there, and maybe missing out on that smirk isn't very important in the grand scheme of things, but imagine that multiplied across most tweets, most people that read them feel something, but the person that wrote the tweet never found that out.

The same thing happened with Luci's thread here - I liked that, I smiled when I read it, but did I tell her anything? No.

Links from this section:

Some signals compress a vast variety of feeling into a tiny thing

Links to this section:

On Twitter you can "like" tweets, or you can reply to them with text, or attach images.

A like exists or it doesn't, it's 1 bit of information to represent all the limitless ways of expressing what we feel. Compare that with all the wonderful languages people can speak.

And what does a "like" mean, exactly? Some people use them for bookmarks, some just like every reply they get, sometimes they mean "yes I like that", or "that's funny", or any number of things!

But we only get 1 way to express all of them.

You can mean many things by a like, and someone else can read many other things into your like.

And on Facebook, they have 7 different reactions:

Heart, laugh, gasp, cry, anger, thumbs up, thumbs down - that's all you get to try to express all the different emotions humans can have. I don't know how many emotions we have, but I'd say there are a lot more than 7 of them.

I'm not saying likes and reactions are bad or that they shouldn't exist, just that they're not enough.

Clay Shirky again (pdf), in A group is its own worst enemy:

Groups [and people, and social interaction itself] are a runtime effect. You cannot specify in advance what any given group will do, and so you can’t instantiate in software everything you expect to have happen

At the risk of sounding pretentious:

There are more things in heaven and earth, Horatio, than are dreamt of in your philosophy

Friendships come from *lots* of small, *repeated* interactions with *people*

Links to this section:

Simon Sarris has a really good thread about how you (normally) form friendships with people (he makes a lot of the same points in this blog post):

The loss of friendship in modern life is wrought by this: Deep friendship takes time.

Time: consistent, repeated small interactions with people in unplanned settings. You cannot set up what would amount to 5 minute meetings with all the people you may someday be friends with.

But you COULD live in a small walkable village or town where in your daily walking to work, the cafe, the pub, the grocer, etc you come across dozens of people over and over, enough to become familiar, friendly, and perhaps interested in each other.

It cannot be replicated in car-centric world, where its only easy to have groups like "school friends" and "work friends". When people speak of remote hurting socialization or chance meetings, I note almost all other chance meeting places are already lost [links to this thread from Paul Graham about how there aren't chance, unplanned meetings when you work remotely]I think what we must come to value again is not making friendship compounds or aiding chance work-meetings, though both are great things. What we badly need more of are unplanned interactions between people pre-friendship, available in other contexts. The new village.

Today I live in the vestige* of a village in New Hampshire. It is greatly cherished, everyone loves it, but none think of expanding it or making new ones. Why?

*It's population density is lower than it was 200 years ago.

The only other village I (we) have is Twitter.

So, we get the concept of "third places", places outside of your home and your work where you can regularly meet people, like a cafe or pub, or a church (as opposed to Marc Auge's non-places). Maybe even a baugruppe.

Because of that thread, I've started going to a cafe quite close to my house every weekend - they make what I think is the best hot chocolate (their secret is it's only melted chocolate (probably Lindt) and milk!) - and joined a bowls and tennis club. One day soon I'll work up the courage and go bouldering too.

[weeks later: I did! I go every week now, I've joined a 2nd tennis club because the 1st doesn't have floodlights so you can't play in the Autumn/Winter, I'm trying to join an amateur dramatics group, and an ultimate frisbee team when they start up again next year; even the impetus for that comes from repeated small interactions, someone from a Zoom bookclub I joined mentioned he played it a few weeks in, I'd been looking for a team sport for a while, and realised I'd like to play it]

This is the same point David Roberts made in his Vox article:

I read a study many years ago that I have thought about many times since, though hours of effort have failed to track it down. The gist was that the key ingredient for the formation of friendships is repeated spontaneous contact. That's why we make friends in school — because we are forced into regular contact with the same people. It is the natural soil out of which friendship grows.

This study isn't it, but it's similar, to wit:

The researchers believed that physical space was the key to friendship formation; that "friendships are likely to develop on the basis of brief and passive contacts made going to and from home or walking about the neighborhood." In their view, it wasn’t so much that people with similar attitudes became friends, but rather that people who passed each other during the day tended to become friends and later adopted similar attitudes.

And this also reinforces the point:

As external conditions change, it becomes tougher to meet the three conditions that sociologists since the 1950s have considered crucial to making close friends: proximity; repeated, unplanned interactions; and a setting that encourages people to let their guard down and confide in each other, said Rebecca G. Adams, a professor of sociology and gerontology at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro. This is why so many people meet their lifelong friends in college, she added.

Christopher Alexander, in the 68th pattern in his incredible architecture book A Pattern Language, Connected Play:

A typical suburban subdivision with private lots opening off streets almost confines children to their houses. Parents, afraid of traffic or of their neighbors, keep their small children indoors or in their own gardens: so the children never have enough chance meetings with other children of their own age to form the groups which are essential to a healthy emotional development.

He makes my point for me far more explicitly in 129, Common Areas at the Heart:

No social group - whether a family, a work group, or a school group - can survive without constant informal contact among its members.

Saffron Huang, applying it to the Internet

Thinking about Jane Jacobs' Death and Life of Great American Cities and how her sidewalk contact ideas apply to online communities: Lively communities of actually diverse people don't form in a landscape of silos, where buy-in is all or nothing - you need gradients of intimacy.

If people can float through, loiter, casually chitchat -- microinteractions they're not bound to, you'll get diverse, surprising interactions. What's more, people will be actually willing to have those convos. Each interaction is low commitment/trivial, but effects add up hugely

You can't float through or check out a gated Slack or Discord. People want to have gradients of intimacy, where you can interact at different levels of commitment, and maintain, decrease or increase it however you like -- the magic of public city life

Lots of well-intentioned people want to start online communities these days and make everyone be best friends, but its full of friction/not super fun to be thrown into a big group chat of strangers and be asked for your life story and commitment to weekly meetings

When sharing is all or nothing, the more common outcome is nothing. Furthermore, it's segregating and leads to little surprise/diversity when people do choose to share it all.

How can we make online communities more like a lively city sidewalk?

Twitter is one of the better platforms for this right now -- different levels of intimacy are possible. Massive accounts or small alts. Instagram normalizes microinteractions but they're low-substance (eg heart emoji on a friend's story). Discord/Slack/Facebook are default silos.

More and more, I think there are connections between Alexander, Jacobs, Walter Ong and James C. Scott's works, they all seem a bit related in my mind, Alexander and Jacobs especially.

Lots of people are having similar thoughts to Paul Graham there (including me, I've fleshed some of these out myself in this post) (all of these I copied from Branch's homepage) -

Ryan Hoover:

Question for distributed teams:

Have you ever hosted a regular happy hour, lunch, or hangout with your teammates over video chat? Curious how others replicate the serendipity and fun of working together in the same office.

What is the WFH-equivalent (they can’t ignore u) of walking to someone’s desk to chat about topic that needs an immediate response: Call people via slack/phone?

Social barrier to interrupt a weak-tie is pretty high, but seems like there is a need for such a communication tool

It seems pretty obvious that after the initial euphoria that remote work for everyone is actually possible now, there’s going to be some sort of reaction in the other direction. Best quote on this from a friend: ‘on zoom you have no peripheral vision’. You can’t overhear or chat

How do you mark that you've started work for the day to your co-workers? In traditional office setting it'd be coming through the door, making coffee at the pantry etc. How do you do it remotely?

Software idea for CEOs only: the ability to virtually replicate coming up to your desk and asking you non-urgent questions while you’re working on something important.

What's communicated vs when, with who and why

Links to this section:

I can split up the differences into 2 categories:

- when, why, and with who you communicate - these differences are far more complicated than what's communicated; you really need to think about them, there can be a lot of unintended consequences here.

- what you communicate - these differences are simpler, and probably easier to fix, you don't need to think about them as much.

Links from this section:

When, with who and why you communicate

Links to this section:

People complain about how Youtube, Facebook, etc are just platforms that spread hate and misinformation, but an important point there is missed fairly often - people are the ones that use Youtube and Facebook, they're the ultimate problem there (I didn't mean for this to sound so totalitarian..).

Adam Elkus talked about this recently (I think with Sonya Mann), but he deletes his tweets fairly regularly, and I didn't back what he said up, but it was something like:

Some people don't like other people on Reddit (right-wing people), so they get them kicked off Reddit, have their subreddit banned, because they think that will make the problem go away, like the platform is the only issue, that the people don't exist, that they don't have agency. But in reality, the people involved have their own wants, their own motivations, and they won't like it when you ban them, they'll go off and start their own social networks where they won't get banned, like Parler. People exist independently of social network platforms.

Julian Sanchez has said the same sort of thing:

In virtually every claim like this, you could replace “Facebook” with “connecting people.” Not that FB doesn’t deserve the crap they get, but the intensity of it feels a little like a form of denial—if not for the wicked algorithms, we would’t be doing this.

It is admittedly depressing to think a descent into psychotic and violent conspiracy theories is just a concomitant of widespread, low-friction connectivity, but… it probably is. This stuff spreads on all sorts of platforms, even without algorithmic boosting.

The underlying problem is this is the type of content that increases engagement. That means, sort of tautologically, that it’s what people are going to engage with absent aggressive intervention to prevent that from happening.

In Ye Olden Dayes, the “intervention” was the (in this one respect) benign paternalism of media gatekeepers. That’s not really a tenable strategy anymore, AND we’ve got at least one legacy gatekeeper that’s decided it’s more profitable to act as a gateway to the hard stuff.

On social media, the “intervention” is moderation, and by all means, the platform should do more of it, especially for non-English content, where they’re much laxer. But lots of human communication is unmoderated, and nobody really thinks that shouldn’t be the case.

Thought experiment: Say we have a bunch of fully decentralized social networking apps built on open protocols, with a wide array of content discovery algorithms and content filters that users themselves can choose between. No evil corporation is manipulating us. What happens?

Tautologically, the people who choose the algorithms that yield the highest engagement are the most engaged, sharing the most content, etc. What yields the highest engagement? Right. Back where we started.

To the extent that it still makes sense economically & technologically to have these functions centralized, the platforms provide a chokepoint that can slow this dynamic down, and they can vary in their willingness & competence to do so. But the tautology wins in the long run.

That is: the networking mechanism (whether it’s one of many platforms or a decentralized protocol) that yields the highest engagement will be the one people are most engaged with.

I think what the platforms do is emphasise particular ways of talking to people, and de-emphasise others, and that is something we can change if we design our platform carefully and properly.

Tumblr is a particularly bad example.

Links from this section:

What's communicated

Links to this section:

A lot of this difference is just "using writing/text to communicate" vs. "speaking out to another person".

I'm going to quote from Walter Ong's fantastic book Orality and Literacy a fair amount here - the entire book is about how the shift from orality to literacy changes people and cultures, it's relevant to what I'm talking about.

Ambient Intimacy

Links to this section:

John Bjorn Nelson has talked about something related to this, ambient intimacy.

Links to this section:

Links to this section:

Links from this section:

Links to this section:

Links from this section:

Snapchat

Links to this section:

Links from this section:

Broadcast

The biggest difference to face-to-face communication on Twitter and Facebook, I'd say, is how what you say is nearly always broadcast to the entire world, whether or not you wanted that to happen.

Anyone can (easily) talk to you, and you can talk to anyone

This one is fairly obvious: on Twitter, and most likely on Facebook too, anyone in the world can send you a message, whether that's a tweet or a post on your feed, and everyone who follows you or is your "friend" can see it.

Neha brought this up recently:

Discourse on internet is broken. Don’t think it will ever be fixed in the way people expect it to.

Saying even the most inane thing on internet in public mode generates an unmanageable amount of misengagement (threats/doxxing/hate) if things catch 🔥. This is a negative experience for most people. This can be improve but will never cease to be an issue.

Discourse on the internet right now is quite a bit like everyone putting all their variables in the global namespace and not getting the outcome they want and the chaos that follows.

[..] We need to spend more time on mutual spaces of trust away from social media that are small by design. (Think I am taking to myself here). Need something hybrid which could be a combination of people we know and people we want to know hanging out in mutual spaces.

The know all, care about all, dunk all living is exhausting. Both the positive and negative of the discourse is exhausting. The infinite topics of engagement are not human scale.

One more thing that sort of hurts the makeshift mutual spaces is regurgitatation of what people saw on social media. It is counter to the separation and useful “slowness” that is helpful for sticky realizations vs trend and building any group intimacy.

But I don't think is completely right, I think it's more precise to say anyone can talk to you really really easily, with no friction at all, on Twitter - technically, IRL you could fly around the world and talk to someone, but most people thankfully don't.

It's the lack of friction that's the issue, I think (thanks to Sonya Mann for linking to that article here)

Here's a recent example - again, please try to ignore the object-level issue. Thousands of people dunked on that guy, but 90% of them had probably never even heard of him before that. To them, it probably felt a tiny thing, but to him it could've been more like a pile-on.

Here's a pretty benign instance - in my ideal world, this would not have been reported on by a major world newspaper.

It's gossip at scale.

This isn't just a bad thing, you can discover so many people through it

Links to this section:

Simon Sarris again has some really good thoughts on what can happen when anyone can talk to anyone:

For most of history one talked to more people, sometimes in a day, than one would ever read in a lifetime. Today we read, watch, & listen to more recordings of people than we will ever have conversations with.

This difference birthed modern ideologies. I think it under-studied.

The internet has started to reverse a trend that began with the printing press. After a four hundred years of declining public sphere, Twitter among others brought us a new Agora. I think the value of this change is hard for us to comprehend because it has been gone for so long.

The intellectuals of Twitter are not the celebrities, scientists, journalists, comedian podcasters, academics. They are the mass of anons and little accounts, people willing to think out loud, doubt publicly, and use the gifts of anonymity or sincerity to speak true sentiments.

By mixing these people, Twitter becomes a check, however small, on ideological thinking. It also offers you the chance to befriend those who are doing, living and flourishing. It is the easiest way to publicly think and do, and by these acts, perhaps you will find your people.

I once wrote that "I don't think even @jack fully appreciates the nature of the thing he has built. He is still concerned with just who should be promoted, or who might best be an arbiter of truth or content, over other ways of organizing the platform. A careful lesson from before the age of print may give us a better answer, if we can find it."

I still think that's true. And I worry that the curtailing of replies may destroy part of what makes Twitter different from a broadcast machine. [links to here]

I understand why some people welcome the feature. Plenty of people today gave compelling reasons to want to reduce the public nuisance burden.But we are witnessing the very slow closing of a large door. This isn't the first new feature modulating replies & it won't be the last.

I hope Twitter seriously considers what they are doing, but I think it will be easy to pass over this quickly. Less nuisance, happy celebrities, maybe engagement even stay the same. What we lose is much more subtle.

How many of you do I follow because of some comment on a public voice? How many others have you found this way? How many brilliant people sit a while on the shore of nothingness, because they have no popular friends to retweet them, then decide Twitter isn't worth it?

It sucks to be a person continuously dogged by crappy people on this site. I know it happens.But it also sucks to be a strange weirdo with no friends and no way to find your people. Twitter is a great platform but discoverability is very, very low. Now its a little lower.

One problem with ideologies/cults is that ppl in them rarely see the outside. On (political) bad tweets its nice they come with an army of fact checking + doubting replies. It's a check on ideology and unhinged-but-popular ppl generally, & it lets others know that doubt exists.

I think a compromise for a feature like this is an option that would auto-hide and auto-mute non-mutuals, where anyone could click to see those replies.This would combine and be more useful than the previous manually hiding replies feature, and less squashing.

An example of using this feature so people cannot publicly doubt: [links to here]

Twitter is awesome and I'm surprised more people don't think so. I've made more friends on Twitter than any other social network. It's easily the most intellectual social network.

If you follow good people, and you post sincerely yourself, then Twitter is a shimmering agora.

Elle has said something pretty similar:

[being able to just talk to anyone at all is] one of my favourite things! I love love love that twitter provides a completely equal footing for everyone from almost every possible background; if you speak the same language and have internet then you can be friends.

one of the loveliest things about this website is encouraging separate friendship groups to interact + merge for the first time

the dynamics are fascinating and beautiful

Links from this section:

Almost everyone I've mentioned here I found through Twitter

Links to this section:

Here's a good example: almost every person I've mentioned, copied too much of, or talked with here, I found on or through Twitter:

- A donkey - https://twitter.com/choosy_mom

- Christopher Alexander - he doesn't have a Twitter account, but people on there told me about him

- Jonah Bennett - https://mobile.twitter.com/BennettJonah

- Daniel Cook - https://mobile.twitter.com/danctheduck

- Michael Curzi - https://mobile.twitter.com/michaelcurzi

- biblically accurate devil - https://mobile.twitter.com/lil_morgy

- Nadia Eghbal - https://twitter.com/nayafia

- Adam Elkus - https://twitter.com/Aelkus - it bears mentioning, Adam is probably one of the most intelligent people I've ever read, he knows so much about so many different topics, connecting things I never would've imagined are similar, it astounds me. I doubt he'll ever read this, but, like I say in "Permanent eavesdropping" elsewhere on this page, if he does, this will be very weird for him to read, I've replied to his tweets once or twice, but he has no idea who I am, and here I am praising his writing.

- Elle - https://twitter.com/ellegist

- Benedict Evans - https://twitter.com/benedictevans

- Tim Ferriss - https://tim.blog/2020/02/02/reasons-to-not-become-famous/ I think I found through Adam Elkus or Sonya Mann

- Antonio García Martínez - https://mobile.twitter.com/antoniogm

- Maria Górska-Piszek - https://twitter.com/made_in_cosmos

- Tanner Greer - https://twitter.com/Scholars_Stage

- Mason Hartman - https://twitter.com/webdevMason

- David Heinemeier Hansson - https://twitter.com/dhh/

- Daniel Howdon - https://twitter.com/danielhowdon/

- Saffron Huang - https://mobile.twitter.com/saffronhuang

- Jacob - https://mobile.twitter.com/yashkaf

- Luci Keller - https://twitter.com/itsLuciKeller

- Kirsten - https://mobile.twitter.com/Kirsten3531

- Matjaž Leonardis - https://twitter.com/MatjazLeonardis

- Sonya Mann - https://twitter.com/sonyasupposedly

- Neha - https://twitter.com/__Neha/

- Richard Nicholl - https://mobile.twitter.com/rtrnicholl

- roobz - https://mobile.twitter.com/tishray/

- Walter Ong - also doesn't have a Twitter account, because he died in 2003, but I still found him through there, Antonio García Martínez mentioned his incredible book Orality and Literacy

- Roobz - https://twitter.com/tishray/

- Julian Sanchez - https://twitter.com/normative/

- Simon Sarris - https://twitter.com/simonsarris

- Noah Smith - https://twitter.com/Noahpinion

- Ari Schulman - https://twitter.com/AriSchulman

- Clay Shirky - https://twitter.com/cshirky

- Zeynep Tüfekçi - https://twitter.com/zeynep, a fantastic journalist

- Sherry Turkle - https://twitter.com/STurkle, through Clay Shirky

- Venkatesh Rao - https://twitter.com/vgr

- Visakan Veerasamy - https://twitter.com/visakanv

- Peter Wang - https://twitter.com/pwang

- Wiskerz - https://twitter.com/wiskerz

- Wesley Yang - https://twitter.com/wesyang/

- Qiaochu Yuan - https://twitter.com/QiaochuYuan

- Michael Zimmer - who I found through https://mobile.twitter.com/worm_emoji/status/1340701274468192256

- Aram Zucker-Scharff - https://twitter.com/Chronotope/

- Devon Zuegel - https://twitter.com/devonzuegel

One notable exception is the best blog on the Internet that I keep annoying my friends with, SlateStarCodex - I think I found him through Reddit.

Normally, your conversations are with a few people, in a specific context

Links to this section:

Last week, I was over at a friend's house, and one of my friends, Ned, made a terrible joke - another person that was there laughed, I grimaced. I don't think I'm exaggerating to say that if I publicised what it was, and who said it, it could ruin his life - anytime a possible employer Googled his name, the extremely dark joke would appear, beside his name, and probably beside a big photo of his face, too - and he'd have no chance of being hired.

And that doesn't matter at all, because Ned said it in-person - I bet no one else that was there even remembers that he said it. But if he'd said on the Internet, it could've easily leaked out into the outside world, even completely by accident. Someone that wasn't initially involved, doesn't know the context, doesn't know that it's completely a joke, one that Ned didn't mean at all, they could read it and get angry, and they could set about destroying my friend.

Quite a few times, when I've been talking to friends on Facebook Messenger, I've said something that a normal person could interpret as harah, or nasty, that sort of thing, but I didn't mean it like that, and my friends will say something like:

We know you Nathan, we know you didn't mean it like that

And whatever I said is just forgotten about.

In one of my private chats, one friend said this about another:

we all know you have a heart of gold and I always enjoy your sharp honest remarks

Friends know what you, understand the context of what you say, understand what you actually mean, give you the benefit of the doubt, and (hopefully!) give you some slack. Strangers probably won't.

Similarly, text messages don't have any tone in them, but that's not as much of an issue in private chats with friends - they'll know what you mean sometimes, even if they can't hear your tone, since they know you, they know the message's context.

Here's an example of what Tanner Greer said, from a chat between Sonya Mann and Adam Elkus - he deleted his tweets, and I recorded them here beforehand, but out of respect to his deletion policies, I'll paraphrase:

the more popular a tweet is, the more likely it is that you'll regret posting it

social media networks' biggest flaw is that giving someone more attention means they're a bigger target

if a network was properly designed, it would create a situation where, if a post leaves its enclosure, there would be positive (or at least neutral) consequences, instead of negative ones

[..]

Whenever I get a popular tweet, I lock my account, normally for less than a week

[..]

I get as much attention as I want, most of the time, and I'm happy with the kind followers I have - it's not usual to have so many and for them still to be well-tempered and generous

the problem is the more that a tweet reaches outside your usual "audience", the more likely that it'll attract people that see you as something they don't like, and try to punish you for it

As to why that happens, @generativist discussed it in detail.

Wes Yang saying that:

I assume that people know that when I post cringe with a neutral descriptor, there is an implied raised eyebrow, which is usually true until I get rt’d into timelines beyond my typical audience and then I get replies from those who think I agree with the cringe

Here's a hopefully-not-controversial example - a British man says

He should have bitten your arm off for what you were offering

and Twitter, an American company, temporarily bans him for

You may not engage in the targeted harassment of someone, or incite other people to do so. This includes wishing or hoping that someone experiences physical harm

"To bite someone’s arm off" is British slang that means something like "really wanted to accept that", a bit like "jumped at the chance to .." in this scenario, but Twitter isn't British, it's American. They don't understand British slang, so they lock a British man out of his own account because they can't understand him.

But if this was in-person, he'd be talking to (most likely British) people in the UK, and they'd understand him no-problem.

And he can't easily fix it, either - since Twitter is so popular, the moderation here is automatic, there's no person to appeal to.

When is "Die Bernie" not threatening violence? When it's in Dutch, and "die" means "that".

To quote Kirsten:

[I] can't help but think of when ... had a tweet go viral this week

we all knew the context (she was teasing her boyfriend who knows everything about Rome) but the 50k people who liked it did not

As Antón Barba-Kay says:

[A]s online communication makes it easier to broaden and multiply the audience ... it also abstracts us from a body of considerations governing the rhetoric and substance of other media: Who is speaking and why? Who is being addressed? What expectations are being adhered to or defied? What is the manner and likely tone? We speak online in the relative absence of circumstances by which we take our bearings to understand words on a page or overheard.

Most problems with and criticisms of online communication, most apologies for misunderstanding, or defenses of past remarks, make their way back to the problem of context, the problem of how to take someone’s words. In one way it’s obvious why this should be so. As ready access to all manner of views and sources has increased—and as information is so readily copied and repurposed online—some of it is bound to be misconstrued. But context is also different in kind from what we usually mean by information: information is a matter of factual content, while context is what informs our sense of how we should respond to it.

We're all guilty of mistaking the context, I'd bet. I definitely am, and I very nearly didn't recognise that I was doing it myself. I just felt some righteous anger at a person for saying something I didn't like. Days afterward, probably because I'd written this, it popped into my head that maybe what she meant by what she said isn't what I read, that she said it in a different context, where it means something else - as in, maybe she was talking to her friends, and I read it, not understanding how they talk to eachother.

For example, the word fenian can be used as a slur in Ireland, referring to Catholics or Irish nationalists, but it also means a member of the Fenian Brotherhood, an Irish Republican organisation in the USA in the 19th century. You can very easily see someone talk about "fenians" and get angry, when you don't understand that they mean the Brotherhood.

I imagine this is more likely to happen the more emotional a word is used - the hotter it gets people when they read it, the less likely a person is to stop and think "but what context was this used in? Do I understand the context?" - you can think yourself of a particularly rousing word, which I won't mention to avoid poisoning this essay with a political slant, oil spill model of polarisation-style.

The Internet is worse when you're popular

Links to this section:

Visakan Veerasamy and Tanner Greer have both said Twitter gets noticeably worse the more people that follow you; Veerasamy:

you have 58 followers, Dr. Taber has 33,600

in my experience, "happily answer questions" is something that a normal person can handle up to about 5,000 followers, beyond which keeping up means your personal life has to take a hit

I’m always looking out for examples of people talking about signal vs noise filters,& every time (50-100+ egs by now) someone suggests better filters, they have significantly fewer followers than the person they’re suggesting it to

Past some threshold (100k followers?) the disincentive for being smart in public becomes inhibiting/debilitating - & at that stage your private networks are full of gold, so you don’t need to use public spaces this way anymore

I think [asking for clarification and getting blocked] is something that happens when you cross about 100k followers, maybe earlier - the infinite endlessness of people seeking clarification means your experience is the same whether you block or engage

Greer (there's far too much here to quote all of it, I've already quoted too much, you'll need to read it here too):

The twitter user with 500~ followers in some ways exists in a world similar to the blogosphere of old. She is part of a small, self-selected community. Her followers chose to follow her because they are sympathetic with her ideas or at least interested in them. It is not difficult to have open and honest exchanges when you swim in safe waters. Most people in her network know her, and she knows most of them, so there is little incentive for mischief.

This changes with scale.

[T]witter is not a constellation of carefully moderated communities. The users of twitter are one great mass. The ponds and lakes of the blogosphere have emptied into a heaving sea. In this sea, twitter users are linked together, but linked weakly. They are unmoderated, unorganized, atomized—but stuck all together. A retweet can roll through the lot in a day.Communities of a sort still exist on twitter, but they are mashed together in an unhealthy way. Many of these communities will be filled with people whose base assumptions about how the world works are 100% different than your own. That is fine. It is quite possible to talk honestly to people who don’t share your commitments—but of course the way one does this is very different from how you talk to someone whose world view aligns 85% with your own. On twitter you do not get to refine your message for either group. On twitter you project to everyone at once.

This is the first difficulty that comes with a growing follower count on twitter. As the count grows, the number of different communities you are projecting to grows as well. Soon, large numbers of people start to follow because they see you as a representative of a certain strain of thought, or as a key voice in a particular conversation they care about. They are not are sympathetic to your ideas or even merely intellectually interested in them; instead they follow you to keep tabs on what you and people like you are saying. Many actually despise you and your ideas to their core (in twitterese, they are a “hate follow”).

My friend Matthew Stinson described this shift as that point where "interactions stop being inquisitive and start getting accusatory. “Points for my side-ism” becomes a real thing." Twitter's retweet mechanism makes this problem far worse. All one needs is a snarky RT for these people to take what a thought they dislike and BOOM!, project it into communities it was never intended for as the perfect example of what they all should be hating at that moment. [this is similar to what happens with tumblr reblogs, as Scott Alexander has talked about]

Thus if you have a large follower account your experience on twitter goes like this: you share a thought optimized for Group X. Members of Group Y, Group Z, and Group V automatically start sharing it as the textbook example of why Group X deserves crucifixion.

This is what happens in an online ecosystem where the boundaries between communities are gone, and moderators (by nature of the platform's universality) cannot exist. To run a high-follower account on twitter is to be constantly exposed to entire communities whose members will treat you as an enemy to be defeated or a buffoon to be humiliated the minute they become aware of you. People with 500 or so followers (e.g. my girlfriend) are rarely trotted out as the example of all that is wrong with the world. Anyone with a higher follower count knows this is the default state of their mentions on any given weekend.

(when does quotation become copyright infringement?)

And from Jonah Bennett, this time about Clubhouse:

Unlike in person, in Clubhouse, it's very, very easy to stumble upon cultures and groups which have extremely hostile values to your own. This unsurprisingly makes people MAD because they had forgotten or had chosen to forget that this even existed in the same society.

This creates a lot of drama, conflict, and attention which may or may not prove to be in Clubhouse's interest at the end of the day. But something about Clubhouse is fundamentally unnatural because normally you're not meant to see the behind the scenes of other cultures.

These tweets inspired by that recent Clubhouse clip going around where Somali women are going really hard against gays, which people forgot is still very much a thing.

Often, peaceful co-existence is about NOT knowing what the other groups are doing, because they have ways of being and thinking that drive you into a state of madness, which can lead to bad things.

And from Sonya Mann:

one of the best decisions that I ever made was filtering my notifications, because it turns out that once you amass enough followers / become "known" enough there is an unlimited supply of salty randoms who want to yell at you about various things

ppl will post aggrieved replies like "you have personal flaws! I shall now enumerate them!" uh yeah I know, quick question who the fuck are you

There are no communities/places on Twitter

Links to this section:

Twitter used to be called a firehose - everyone sees everything everyone posts, all the time.

You can't form spaces, or places, or even groups of people on Twitter, places where only certain people are allowed in.

People talk about "science Twitter", and "rationalist Twitter", and they don't really exist - they're just sets of people that like to talk to eachother about science or rationalism, but nothing stops them getting invaded by anyone else.

[T]witter is not a constellation of carefully moderated communities. The users of twitter are one great mass. The ponds and lakes of the blogosphere have emptied into a heaving sea. In this sea, twitter users are linked together, but linked weakly. They are unmoderated, unorganized, atomized—but stuck all together. A retweet can roll through the lot in a day.

Communities of a sort still exist on twitter, but they are mashed together in an unhealthy way. Many of these communities will be filled with people whose base assumptions about how the world works are 100% different than your own. That is fine. It is quite possible to talk honestly to people who don’t share your commitments—but of course the way one does this is very different from how you talk to someone whose world view aligns 85% with your own. On twitter you do not get to refine your message for either group. On twitter you project to everyone at once.

For a place to actually exist, it needs to have boundaries, there needs to be a way of limiting who joins it - none of that happens on Twitter, and it can't really happen either, except in a network of private accounts, but those would be very hard to break into - how do you discover it, if you can't see anything they say? If they reply to something you say, you'll never even know.

In 2006, Twitter described itself like this:

A global community of friends and strangers answering one simple question: What are you doing?

Being known by thousands or millions isn't good

Links to this section:

Say only 1 out of 100 people is an asshole, and only 1 of 100 assholes is dangerous. Then, 1 in 10000 people is a dangerous asshole. A lot more than 10000 people can have heard of you on the Internet.

Tim Ferriss has talked about the terrible things that he knows about, or have happened to him, now that he's famous. Quoting it wouldn't be kind.

We're not meant to be this known by that many people.

Twitter isn't anywhere near as bad as what he talks about there, it's far more lower-level, but it's more widespread. I've not experienced it myself, but then I have very few followers.

Similarly (please ignore the object-level issue here, and focus only on the meta-level!), bad things can happen when a popular person on Twitter (in this case, someone with 230 thousand followers), exposes you to their followers:

[by quote-tweeting me, he exposed] my tweets and my account to his hundreds of thousands of followers. I received some very stimulating correspondence from these quote-tweets. Several [..] called me a snowflake; several [..] called me a baby; and one fellow went so far as to threaten me with anal rape

A few nasty people is only to be expected if, like [him], you have 230,300 followers. Neatly, I had 238 followers when I posted last night, so we can conclude [he] has almost a thousand times as much reach on this platform as I do

I'm sure the large account didn't intend for that to happen, and he probably doesn't even know it did, but this sort of thing seems inevitable when you get that popular. "Don't reply to anyone, if you're popular" feels like the wrong solution, though.

230 thousand people being able to be made aware of another person, and the nutjobs among them threatening that person isn't good, but neither is "we're going to artificially only allow 1000 people to read what you say" or "you're not allowed to shine a spotlight on people with less than x follwers".

Also, "don't talk to people if they're popular" isn't a good solution either.

I wouldn't really have a problem with someone being able to write a newspaper column that does something similar, though - maybe because the friction to someone reading it and threatening the person is so much higher, far more than a button click away. I'm very wary of limiting what people are allowed to say, and where or how.

The reverse, you knowing of thousands or millions of people, doesn't seem great either, for more nebulous reasons.

Commenting threshold

Links to this section:

It's like there's a commenting threshold - what you feel or want to say needs to be important enough to warrant a comment, and if it's not, it doesn't get said. It feels like we're missing a large amount of communication because of that.

This sounds stupidly obvious to say, but the easier something is to do, the more it happens. So, since speaking what you want to say is far easier than typing it, I'm pretty sure you're going to speak more than you would type, so the commenting threshold will be smaller if you're speaking.

That's definitely true in my experience, when I send voice messages to my friends on Facebook Messenger, I say far more than I do than in text messages (and they say far more to me when they speak, too).

Just think, how often do you call someone when you want a "proper chat"? Why don't you have proper chats in texts?

Links from this section:

Many tweets are to everyone, and no-one

Links to this section:

Most tweets are to the "void", to everyone in the entire world, but also to no one at all.

Without places, you can't have norms

Links to this section:

If you and your friends were all in the same room, you could have a rule like "we can't say the word 'discombobulate' today", and you can enforce that rule, and kick anyone out who doesn't follow it, like what Peter Wang has said here:

Every conversation is a space. For that space to be generative and not combative, the participants must agree on shared norms.

Without that, you get clashes that inevitably turn hostile, because they are value system conflicts.

Serendipity is then no longer a feature, but a bug

The easiest way of saying this is "norms" don't just exist by themselves, communities have norms, norms are communal norms, and you could think of you and another friend seeing eachother every week as a tiny community.

Usenet users talk about Eternal September - in September 1993, AOL started letting their customers access Usenet, and AOL had a lot of customers. Before that, only a small number of people would start using Usenet each September (coming to uni for the first time, and accessing Usenet through them), so they'd learn and start following the Usenet norms. Few enough people joined each September that they integrated into Usenet's norms; AOL's just kept coming, and overwhelmed Usenet - too many people kept joining, and Usenet couldn't integrate them all.

Twitter is the epitome of Eternal September - it's even worse, because Usenet has newsgroups, where people go to talk about specific things (like comp.theory.self-org-sys, about self-organising systems). Twitter doesn't have categories like that at all, just 1 big category where everyone is.

You can enforce norms in tweets to specific people, but not on untethered tweets - anyone on Earth can reply.

The best example of norm enforcement I can think of is the AskHistorians subreddit - it's heavily moderated, to make sure that only really high-quality answers are allowed - look how many rules they have! They ruthlessly delete every comment that doesn't follow the rules:

The most important thing to understand is that /r/AskHistorians is a space created with a specific purpose, namely to provide a place where users can, quite literally, Ask Historians their questions, and complementary, provide a place where knowledgeable users want to contribute by writing answers to the questions in their spare time. Because popular doesn't equal correct, and because being first doesn't equal being good, the Moderation Team curates the subreddit to ensure that the only content left standing is the content that deserves to be.

Importantly, this is on a subreddit, a specific place, something you could actually think of as a community.

Anything approaching that level of moderation just isn't possible on Twitter, and might not be desirable anyway, even if it was.

Another good example of community moderation is the Brazilian Facebook group Profiles de Gente Morta (Profiles of Dead People), where users collect and discuss accounts of people that have just died:

Moderators play an active role in deciding what happens within the walls of PGM and are responsible for approving all profiles submitted by other members. They are tasked with keeping an eye on heated debates and will step in whenever someone disrespects the dead, like by mocking those who passed away or ridiculing cases of suicide. Each group has a slightly different culture, which is reflected in their policies. Some pride themselves on being “uncensored” and include posts with images of grisly deaths. Others poll members ahead of time about whether they want their profiles to be featured after they die.

The job is an enormous time commitment. “At the very least, I’m there from the hour I wake up to when I go to sleep,” said Ana Bittencourt, a Brazilian journalist who moderates Werle’s PGM group. [..] Bittencourt has lost count of how many notifications she gets in a day.

And another, from the moderators of /r/DeepFriedMemes, on how the dynamics in a community can be messed up by large scale:

We, the subreddit moderators, often became trapped in a cycle wherein the times in which moderation was not taking place as consistently. As a result of this, the sub would become overpopulated with shitty posts, misguided in their understanding of our humor which in turn breeded even shittier imitations.